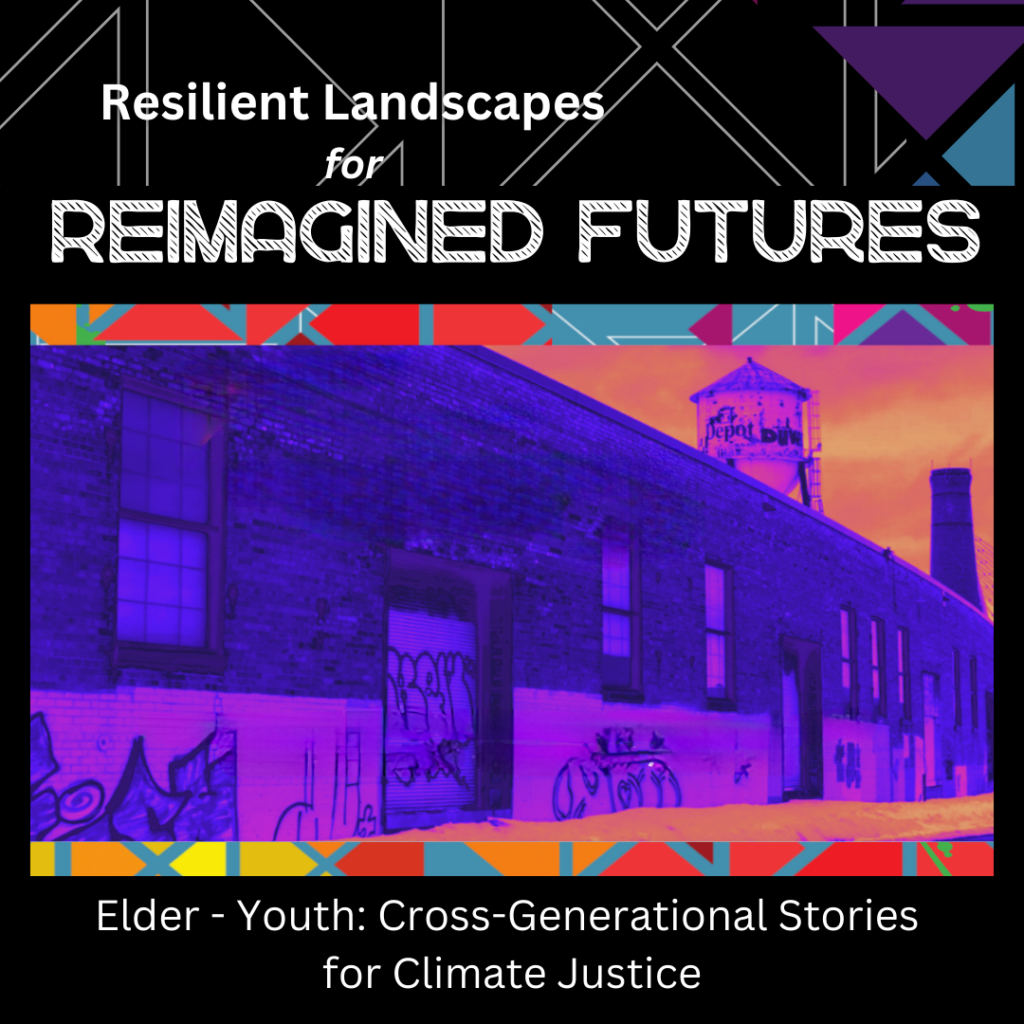

Resilient Landscapes for Re-imagined Futures

is a year-long pilot project to amplify an Elder and Youth’s narratives and their cross-generational visions of climate justice. In support of the East Phillips “Roof Depot” environmental justice community in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and re-imagined futures. This is an effort to redefine ‘resilient landscape’ and whose voices are included in shaping and reimagining these spaces.

Reframing the Narrative

The mainstream environmental movement has historically defined ‘resilient landscapes’ as natural places, rich in biodiversity and ecologically important for conservation efforts. Yet there is a need to think more broadly about what defines a ‘resilient landscape’ and who is included in these spaces. Climate change impacts all landscapes, including rural, urban, and suburban, and people’s lives who reside there.

A Call for Climate Justice

As climate change intensifies, we must be willing to adapt how we define resilient landscapes and include those who have experienced the cumulative impacts of environmental injustice. There is a need to cultivate and amplify sustainable visions, especially those from voices of frontline communities that are disproportionately impacted by climate change but historically excluded from critical climate conversations and decision-making.

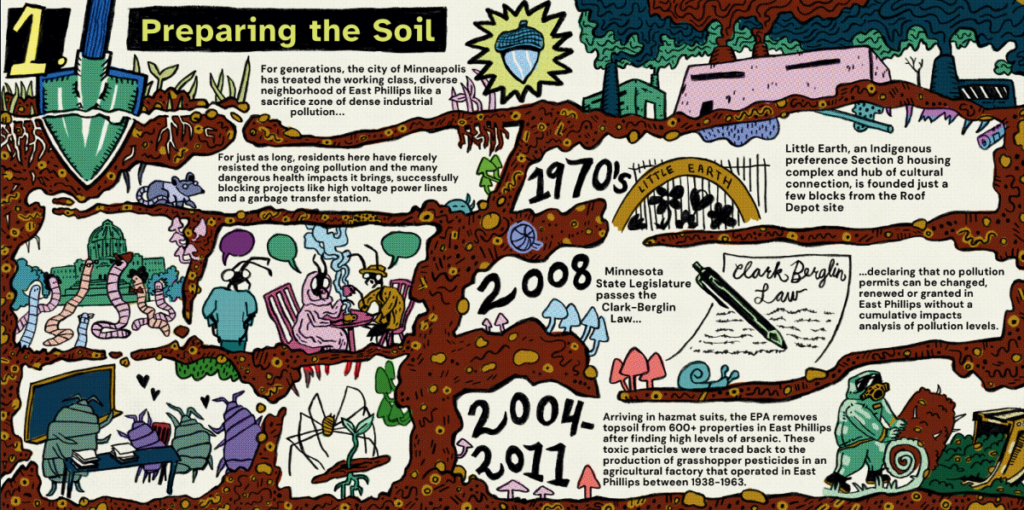

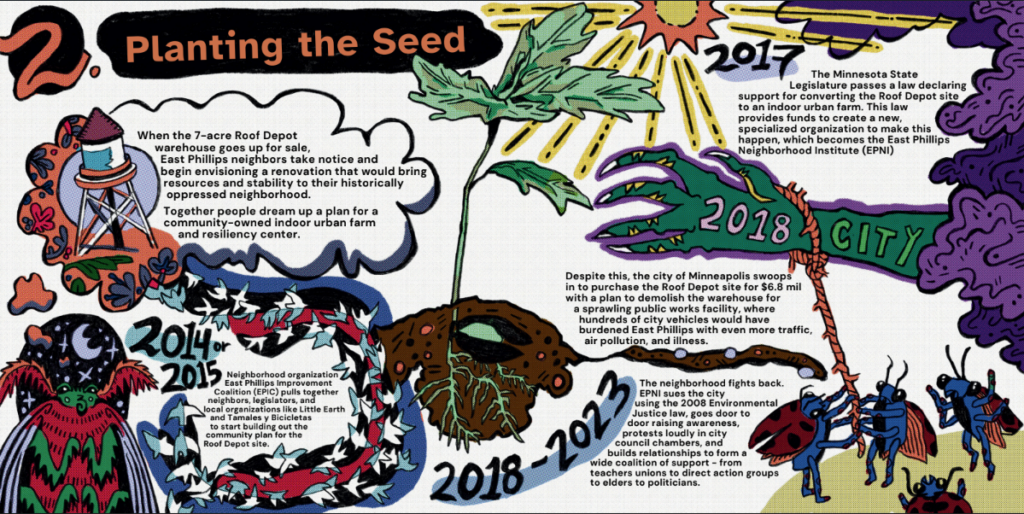

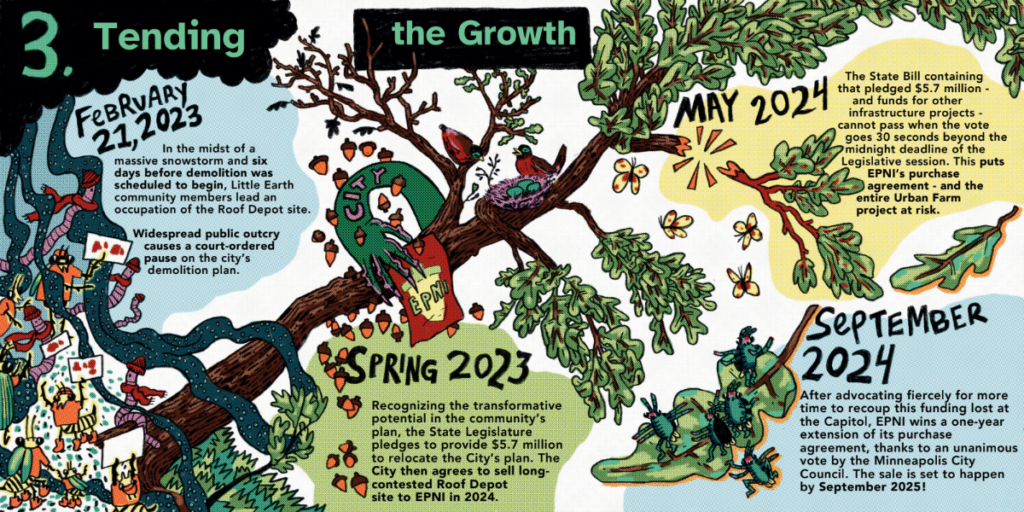

In 2023, the East Phillips Neighborhood achieved a groundbreaking agreement with the City of Minneapolis to purchase the Roof Depot site—an important milestone in the ongoing fight for environmental justice in the Twin Cities. The community’s vision for the site includes an urban farm, a green jobs training center, a community gathering space, and a climate resilience hub to foster long-term sustainability and community empowerment. Learn more through our partners at East Phillips Neighborhood Institute (EPNI), and view the illustrated timeline of history created by Chanci Art for EPNI.

Centering Our Stories

Resilient Landscapes for Re-imagined Futures centers the voices of Lois Long and Kamille W-D as storytellers from East Phillips, sharing what has been and what they want to see—depicted in written stories and through visual artwork, while also speaking to the importance of intergenerational climate conversations for a healthier and more equitable future.

Join us on March 22, 2025 from 2 – 4:30 pm at the East Phillips Cultural Community Center for an Event and Exhibition to engage the broader community to hear these narratives as told live by the storytellers, and through cross generational dialogue between the elder and youth to share their visions of climate justice for a re-imagined future. In addition, the exhibition will include artwork depicting an overlay of their visions for a new future.

Read the full narratives of Lois Long and Kamille W-D. Below:

Lois Long’s Climate Story

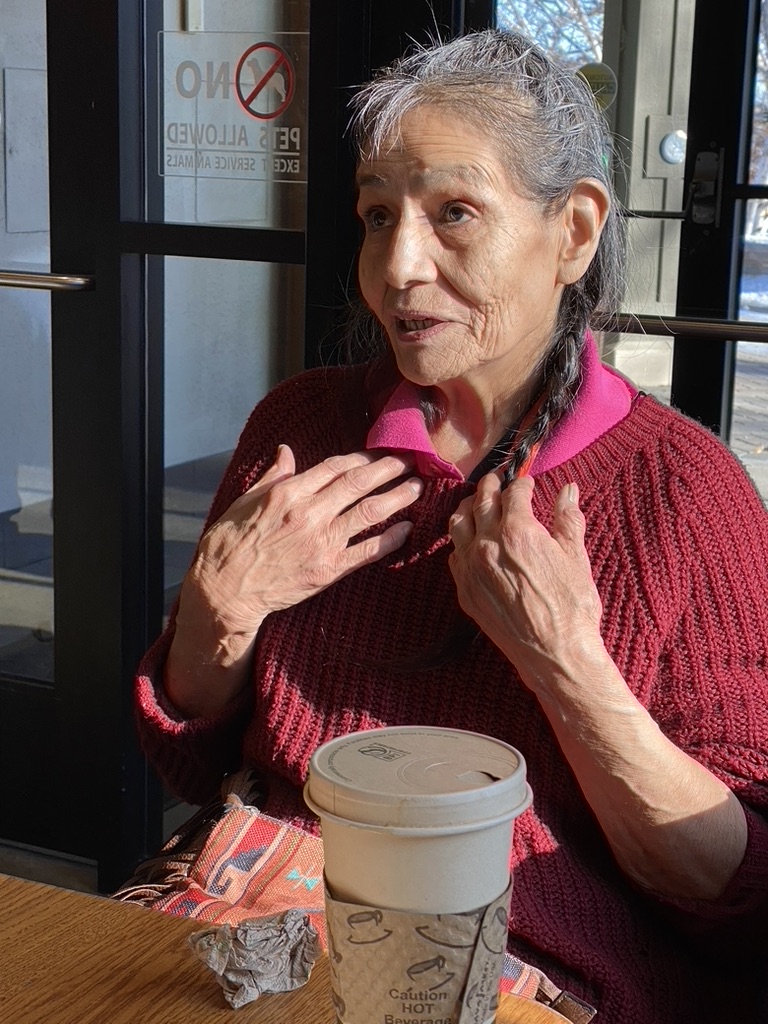

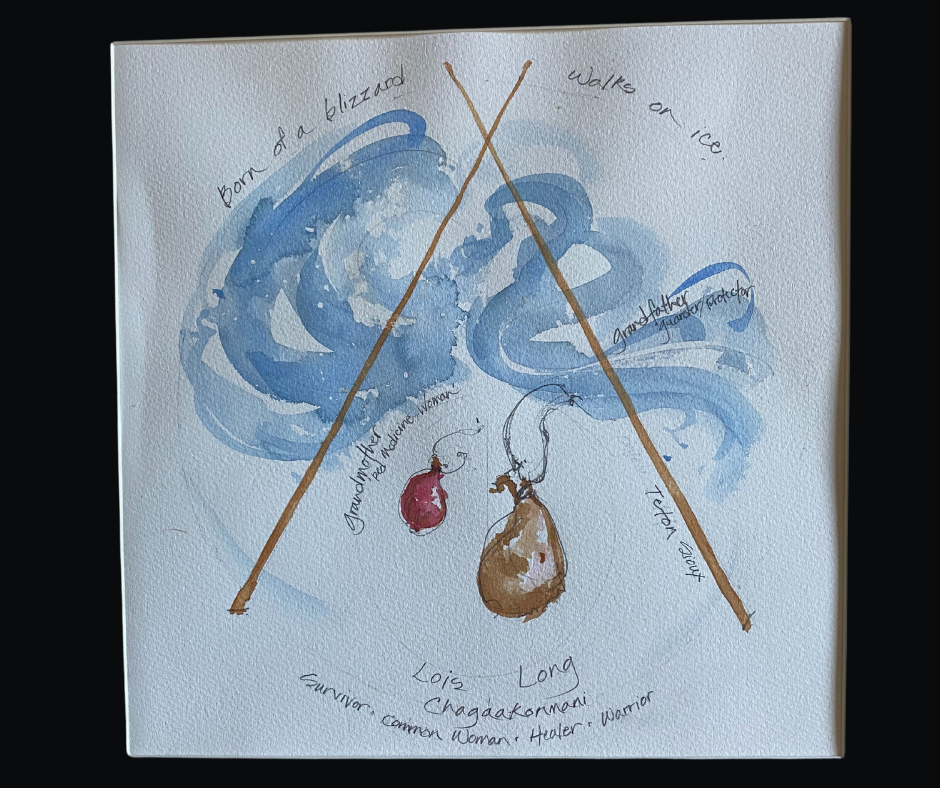

Lois Black Cat Catches Long (1959) is a member of the Teton Sioux, a grandmother, a boarding school survivor, and a resident of Little Earth, Minnesota.

I was born during a January blizzard when the waters were frozen. My grandmother named me Chagaakonmani, which means “walks on ice.” My grandpa was Crazy Horse. I am a mother and a grandmother, and I am raising my granddaughters. I am also a boarding school survivor. I come from a long line of medicine women, healers, and warrior protectors.

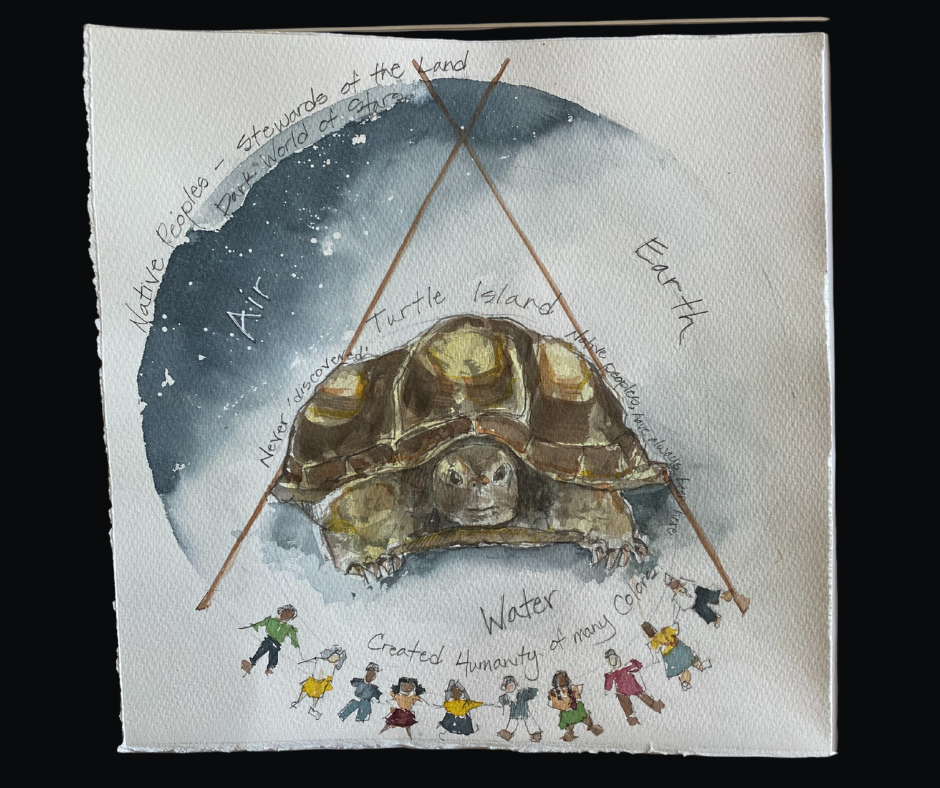

This place Turtle Island, was never “discovered.” We the Native peoples, have always been here. We were created to be stewards of the land, to be healers, and we know how to live according to the cycle of the seasons.

There is a lot more learning to be had in the world today and even tomorrow with climate change.

The Lakota hold many stories about how the world was up to now, it is a past that informs the present and is necessary to understand to envision what will be.

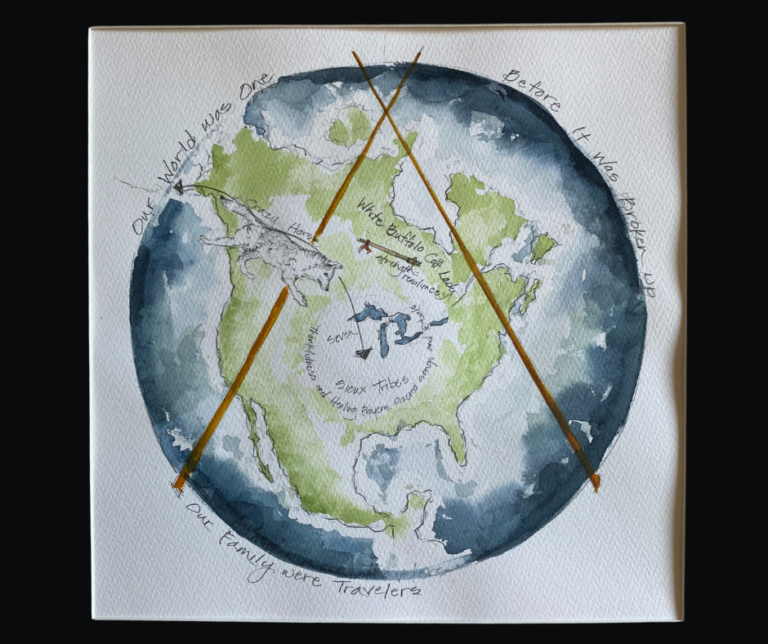

The World Was One, Before It Was Broken Up. In this time, our family were travelers from one place to another. Grandpa Crazy Horse guarded and protected the people. The Sioux were given the pipe to carry, and when White Buffalo Calf lady came to green grass there were certain parts of the Buffalo she gave to certain people because of their healing abilities, they knew there was some terminal illnesses they could never heal with the medicines here and that is why they traveled and bartered across the frozen waters Bering Strait.

Grandpa Crazy Horse’s tribe traveled from here to Canada to Alaska and crossed over the waters to Japan. The heat melted the ice bridge and grandpa Crazy Horse’s tribe could not get back for a long while. Back in the Midwest the seven Sioux tribes wondered where Grandpa Crazy Horse’s tribe went and the thought was that they were so good they must have ascended into heaven and out of this world, because they were gone for a very long time.

Even then the seven Sioux Tribes knew of climate change, too, but it wasn’t what we have now. What happened was that on the way back there was a great snow storm, and the young warrior, Takola, almost lost his life. One night a wolf came to him and told him “I am going to take you home, and you are going to teach your people what I am going to teach you along the way.” So he grabbed the wolf’s tail and they traveled together and every night he brought the young warrior to a cave or place of shelter from the cold and the wolf would sleep on him to keep him warm.

They were hungry, but everything around them was frozen, they couldn’t even find one duck, one rabbit or one fish. The wolf said now is the time I am going to teach you the sacred songs and rituals but first I will teach you thankfulness and healing prayers. Which you will take back to the people, so the people will know that their prayers will be answered if they follow what is supposed to be. The wolf taught him these things so he could live and they made it back home. This knowledge stayed with the people.

When there is illness we have a song and ceremony, called, Hocheka, to ask for healing for the sick, and then thanks is given for the healing. So when the White Buffalo Calf Lady gave the pipe to the Oglala Lakota Sioux, she gave it to uncle Looking Horse at Green Grass to carry because of the strength and resilience represented by our people. These are the stories and knowledge shared, sometimes told through songs, prayers and ceremonies.

My grandma was called Red Medicine Woman. She always carried her medicines in a pouch made of an animal with a red hide, but the pouch wasn’t very good. Then, one day, the White Buffalo Calf Woman came and gave my grandmother the buffalo’s scrotum, a sacred gift for her to carry her medicines in. This gift would help her continue to bring health and life to the seven Sioux Tribes.

Our stories carry the power to save the world. They hold the knowledge of what needs to be done to restore our bodies and our spirits.

We Always Knew The Earth. We grew food before the government told us we could. We grew fruits and vegetables in circles. Western medicines are limited in their healing powers, when compared to the plant and sacred medicines already around us that repair; rosehip, mushroom, cedar, black sage, coffee, willow, oak —natural tylenols. Plants to clean the water and air. Saplings and birch bark needed to make our Tipis and Sweat Lodges. We also have a Covid tea, a recipe passed down from our ancestors, which has been useful today. It’s made from onion and cayenne pepper, helping to open the lungs and nasal passages. Onion is placed in windows and doorways, absorbing germs and cleansing the air as people enter.

It’s important that these ways are not forgotten. We must honor the past to guide us into the future and, in doing so, understand ourselves and each other more deeply, especially in these times.

What is Above Is So Below. When the Creator created the world, He also created what we call the Vortex of Life, Waneatuwakana. He said, Waneawakanso, we come from above, from the holy breath of life. The Creator gave us life, language, and prayer, teaching us how and when to pray through the circles of all our four lives.

The four directions, the four phases of life, and the four seasons all influence our emotions and mental health, helping us understand the meaning of who we are and how to be in this world. The vortex above is known as Wanyatuwuicka. When we are born, we descend through this vortex to the earth; and when we pass away, we return to the skies through it.

The Tipi represents this passage, the sacred journey between earthly life and the cosmos.

The Tipi, and the sweat lodge outside my house, represent the womb—full of water, so when one is born, we are born out of that water. Whenever you are going through something difficult, you go into the sweat lodge to pray and sweat, mimicking going back into your mothers womb and to be rebirthed.

When NASA saw footsteps going up but none coming down, they asked about it. We all laughed and said, ‘again,’ because when you’re born, there are no footsteps coming down. You are born through your mother’s womb into the world. But when you grow old and pass away, you return home through the Northern Lights and the Milky Way. So when we see the Northern Lights, we know those gates in the sky will open.

We all have prayers—every morning and night, we offer our tobacco for safety, for a good life, and for health—not to be rich or famous, but simply to ask humbly to live well in this world. When we see the footprints in the Northern Lights, we feel this deep connection.

We are energy, and what we say is very important because our words reverberate throughout the world. There is a big pull now for the Lakota language to be taught, because the language when not used correctly in the sacred ways can be very detrimental. That’s why we were taught the language, prayers and how to speak and how to pray so that we could know ourselves and each other.

I want to see a more sustainable life; gardening, making herbs and medicines and personal necessities that bring joy and health, and to see artwork in our community, to see in all 38 languages phrases of the Creator. God got tired of being in a dark world with stars, he said I am lonely and this darkness is not enough. So, He created people from clay, representing the many colors of humanity, made from different colors of the earth’s clay.

This is the Creator’s world and it is beautiful, so the pollution brings negativity that affects every aspect of our lives. The lateral violence, homelessness, addiction, and the toxins dumped on the land—like arsenic in the soil where we live. It is evil upon evil, destruction upon destruction.

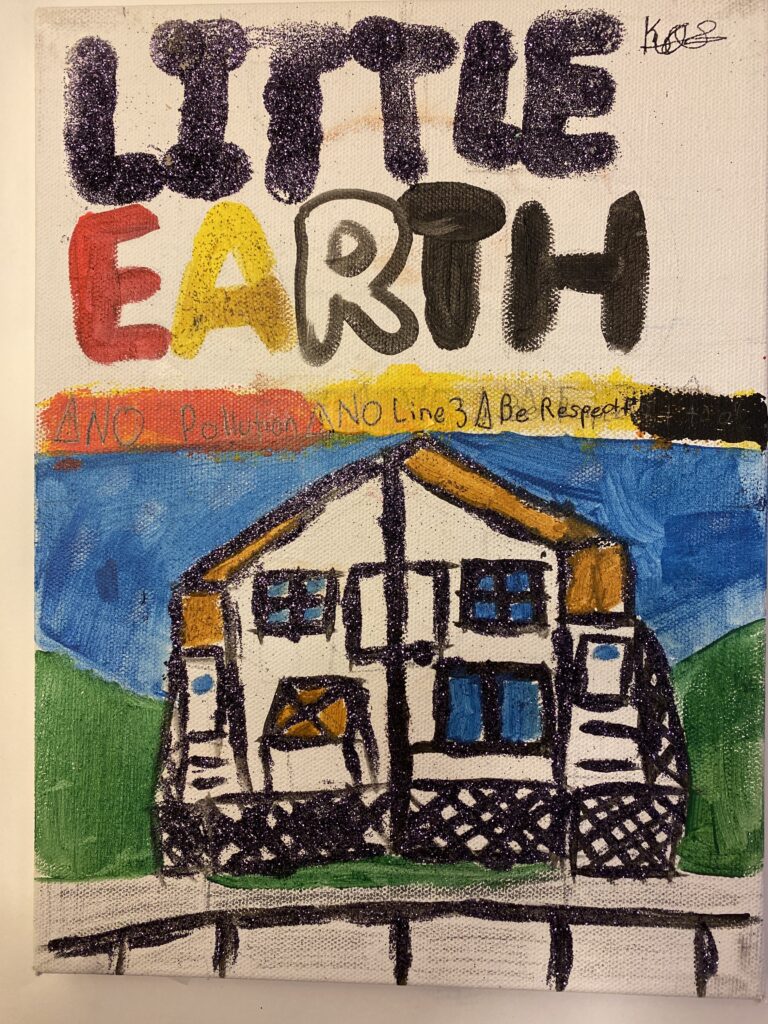

I moved to Little Earth in 2015. My granddaughter has suffered from seizures, our medicine man said that the environment, what we put into our bodies has a big influence on our well being.

Earth

The Arsenic and chemicals in the soil contaminate the foods we grow and the plant medicines we need for healing.

Water

I never knew about the water, but I smelled it was off. Our doctor warned us not to drink the tap water because it contains chemicals and sediments here in Little Earth. One day, Miss Cassie Holmes and her group came through and shared the community’s fight for environmental justice, confirming what we already knew. Now, I pay for clean water, even though I’m on a fixed income because I refuse to risk using water that may still be contaminated.

Air

The air in our community is noticeably polluted. Sometimes the air quality and smell is so bad that I tell my kids to close their mouths and to put their shirts over their noses. Cassie’s crew brought around air quality monitors to measure the pollution, to actually show what is in the air we breathe from day to day.

Fire

The fire today, which is burning off chemicals, is misused. Firekeepers used to tend to the burning to keep things in balance and ensure we lived a good life. Our well-being meant a lot to the Tribe and the Firekeepers who protected us. This knowledge is sacred; the ceremony, prayers, and teaching are sacred and need to be passed down.

Environmental justice would bring the repair that is desperately needed. We should not have to pay for healthy soil, clean water, and air—these are essential for daily life. The responsibility lies with the corporations that have poisoned our environment, not the people who live in it.

Instead, we are left to manage the damage, using inhalers and taking allergy medications like Zyrtec just to alleviate the environmental stressors on our bodies. Some say that Native people don’t exist anymore, because of the violence that tried to wipe us out through genocide and now continues in these other forms.

I was born during the boarding school days. When I was only two, my grandparents taught me to read and write. One of my uncles ran almost 70 miles from Pine Ridge, stole the Dick and Jane children’s books, and brought them back so we could learn how to read in English. I was taken from my family to go to boarding school because I understood both languages. Even through all the darkness of the boarding school days, we could hear our grandpas and grandmas singing way out in the hills for us.

Native people have persisted. They wanted to break us, they wanted us to disappear, they wanted us to be gone off the face of the Earth, but we are here. It is important to tell people that we are still here, particularly Native children, who are very resilient in being alive today. I want them to know we are still here.

A child’s mind is young, curious, and full of innocence. What they think, see, feel, and how they live holds immense wisdom. We must never doubt our youth. The children of today, especially Kamille’s generation, are the seventh generation we were foretold about.

Out of their innocence come the answers and fortitude to move forward into the future. Children may not yet have the knowledge of the older generations, but they carry in their DNA a deep, ancestral wisdom. Science may not yet fully understand how our brains work, nor can it speak to the spiritual knowledge embedded in our DNA. But it’s there—passed down through generations, waiting to be re-awakened.

I want to see a Native school in our community. I want to see a revival of the Lakota language and healing ways and to teach this generation and the next the knowledge necessary for how to be in this world, to address climate change and justice. A place to teach our children the answers that we Natives know and that corporations need. A place where the elders are treated as a community treasure and can come in and share the old stories and teachings meant to be shared.

These days we are still seeking environmental justice.

Sometimes, I feel I must keep my granddaughters inside, so I always have crafts ready for us to do. On days when it feels safe, we go outside to make mud pies, search for fossils, and paint rocks. Imagination and creativity—making things with our hands and engaging their minds—are so important. These simple tools and skills will be essential in their fight to stay healthy in this world.

Even for us adults, play has an important place, to make our gardens and make our yards to create things. To ease the stresses of bills and daily living. This is a big reason I envision murals and artwork throughout the community. Vibrant reminders of our prayers, language, ceremonies, and songs to inspire hope.

Sometimes I laugh when I think of the challenges. But there are times when endurance has taken the form of laughter, as a way to survive. Despite what Native people have gone through, there is still joy and laughter. Because we are still here. When NASA saw those footsteps going up and were confused, we had a good laugh because of what we know…

Because we come from the stars.

Lois Long’s story and artwork have been developed as part of Resilient Landscapes for Re-imagined Futures—a year-long pilot project amplifying the narratives of both an Elder and a Youth, and their cross-generational visions of climate justice. Facilitated by Jothsna Harris of Change Narrative and artist and science educator Julie Marckel, in support of the East Phillips “Roof Depot” environmental justice community in Minneapolis, Minnesota, to support local efforts to foster re-imagined futures. This project is made possible through generous funding from the Earth Rising Foundation and fiscal sponsorship by Oyate Hotanin.

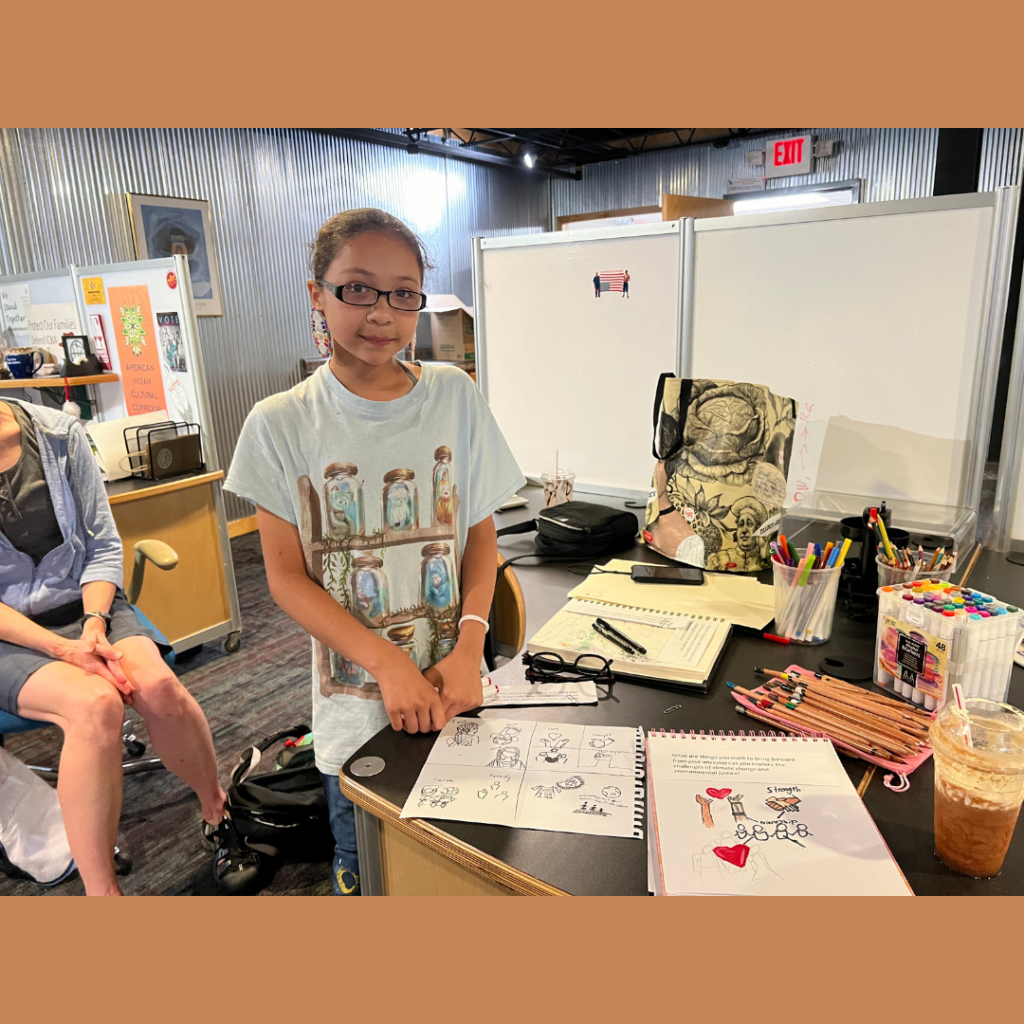

Kamille’s Climate Story

Kamille W-D (2013) is an artist, big sister, Miskwabinesikwe/Red Thunder Woman, and a member of the White Earth and Lac Courte Oreilles Tribes. Kamille’s aunties have been fighting her whole life for environmental justice in East Phillips, Minnesota.

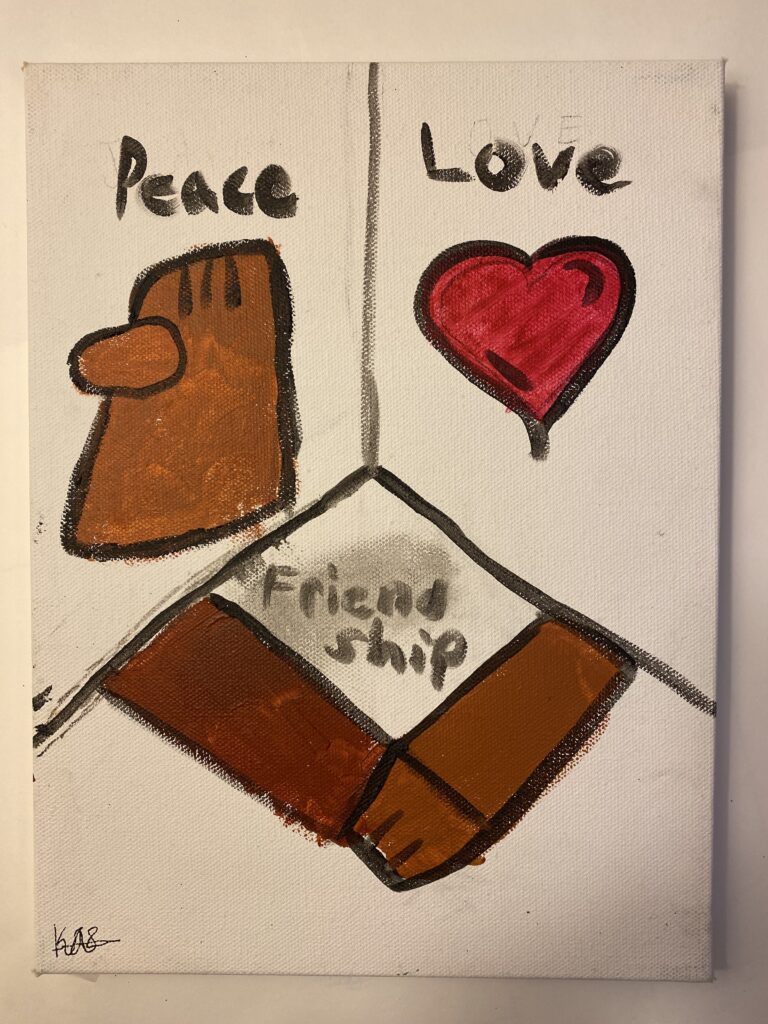

As I think about climate change and environmental justice, I want to bring forward my ancestors’ care, strength, friendship, and their fight. As an artist, I draw hands holding to show this in my artwork—hands of two different people coming together to show care and love for each other, even through their differences. I also draw a fist raised up to represent the fight for justice, a symbol to keep fighting, even for people you don’t know, because justice for everyone matters.

Recently, I moved from Little Earth to another place—everything was difficult with so much going on around our family. The environmental pollution and concerns for our safety were affecting our lives on a daily basis. Our new home is someplace that feels safe and peaceful. There are no sirens to wake me in the night, and I don’t feel scared. I hope I can stay here forever.

I love the community at East Phillips. I also know that being a big sister is a big responsibility. I want my baby sisters and brother to be protected, to be healthy, and when I think about defending them, I feel courageous.

I love my family, and it’s always so much fun when I get to see relatives I haven’t seen in a long time, especially my cousins. One of my favorite memories is when we went out to eat breakfast and then spent the day at Chuck E. Cheese. There was a dance floor that lit up, and we jumped and danced on it, laughing and having so much fun together.

I also have family in the South, and when I visit, it’s always so warm. I love waking up in the mornings and stepping outside for fresh air, or sometimes staying up to watch TV. It’s just a time to relax and chill.

These times with my family make me feel the happiest, the most excited, and so full of joy.

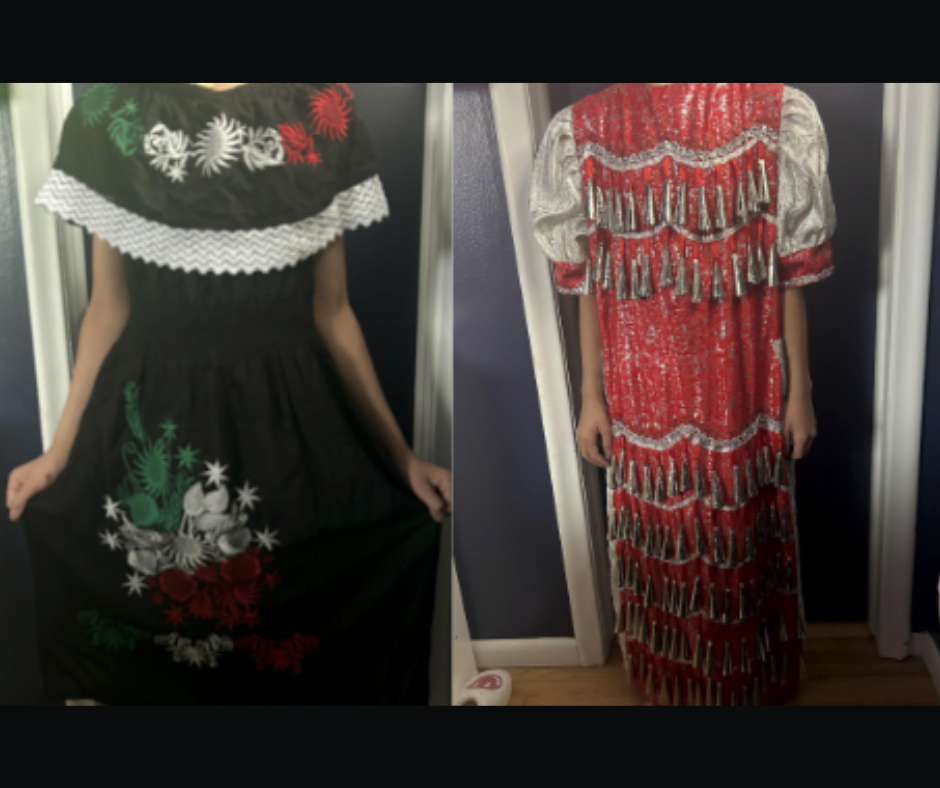

My heritage is Native, Black, and Mexican. My mom is Black and Native, and my dad is Mexican and Native. They each represent different cultures, each special in a unique way.

There are older traditions and rituals that my family celebrates that bring me a lot of comfort, and there are new traditions that I am part of making.

I love to cook and eat different foods, and I know how to cook quesadillas. It’s funny because the name of the cheese I use is called ‘Chihuahua,’ and it makes me laugh. In my version, I put crunched-up hot Takis in the cheese and melt them together between two tortillas. It’s really good.

Pow Wows and Moon Ceremonies are important traditions, as is making ribbon skirts or traditional dresses. I have a Jingle dress, but it’s getting too small. I will make a new dress with fabric, ribbons, and strings with little jingles on them. I pass down my dresses to my little sisters when they don’t fit me anymore. The costumes and accessories of all my cultures are beautiful. I saved up my money to buy a dark black Mexican traditional dress with flowers on it.

There are lots of Pow Wows, and these are usually on the hottest days of summer. I remember once it was so hot wearing my Jingle dress. This year, for the Full Moon Ceremony, it was raining, so we had to move it inside. My grandma says the words for the ceremony. If you have a haircut, you hold that hair in your right hand and tobacco in your left hand. Elders to the youngest, we release them. This is a ceremony for women. If someone has their period, they cannot participate, but they can watch. It is because that is a very powerful time for women.

My aunt is in the Bear Clan, and today I borrowed her earrings, which are beaded with a bear claw in the middle. I wore them because I didn’t have any wolf earrings. My dad is in the Wolf Clan, which means I am in the Wolf Clan too. Each clan has its differences, but one thing bears and wolves have in common is that they are both hunters. My aunt Jolene’s name means Red Bird Loon Clan Woman, and I am still deciding if I should get her these red hummingbird earrings. Sometimes I think about being in the Wolf Clan—wolves like cold climates—and sometimes at night we keep the windows open so it can be cold in the room because we have thick blankets to keep us warm.

My aunties have been fighting for environmental justice in East Phillips for a long time. I remember a protest for the Roof Depot and against another polluting factory called the Smith Foundry. Being involved has been really important for us because most of our family has asthma, and our loved ones and neighbors live in the community, so it matters. I have grown up with these memories and knowing that it matters.

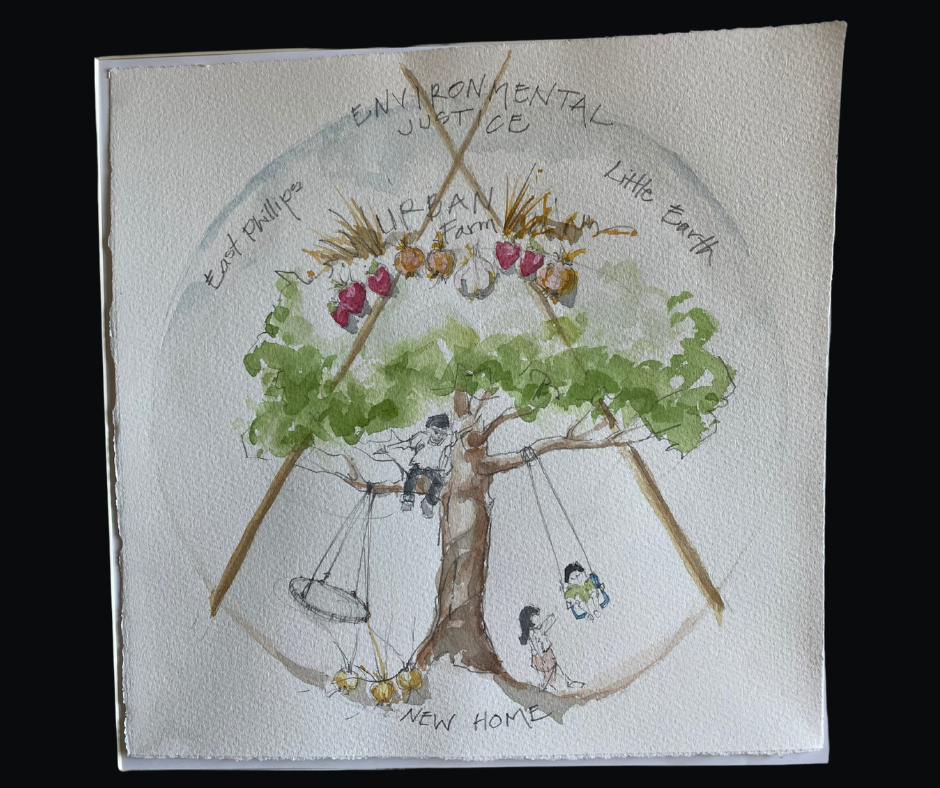

The place I care about the most in East Phillips is the urban farm. I see that when people don’t care for it, it looks like it is dying—the grass is up to my knees, and weeds are taking over the apple and plum trees. Now, the cherry and pear trees are gone. It makes me feel sad. But there are still strawberries, cabbage, onions, and garlic. It is important to have people take care of the farm, weed, and water it so that it can grow. Sometimes kids help out at the farm.

Sometimes I take bell peppers—green, orange, and yellow, sweet ones. There is a tree at my house where I made a garden bed. There are lots of “lemon leaves” growing there. I eat the lemon leaves and play on our swingset. We have a circle swing, which goes round and round and back and forth, and a blue swing for my little sisters. Sometimes they fight over the swing. My brother likes to sit in the tree to listen to them argue. I brought some of the baby onions from the farm home and replanted the ones that needed more growing. I planted them in my garden bed to give them a new home with us.

It’s been raining lately, and that is good. I don’t want the garden at East Phillips to be sad. If it is sad, then nobody can have food.

Some mornings, my family would drive by East Phillips on the freeway. I remember seeing the pollution coming out of a factory. It worried me. But now, I don’t see that pollution anymore because it was shut down.

I don’t remember how, but I know victories happened. I remember that people wanted to buy the Roof Depot building to make something better. Recently, when the new Minneapolis American Indian Center opened, it was nice, and it had a picture of my auntie’s great aunt, Frannie Fairbanks. Even though I did not know her, I know she was important because, under the picture, it said “in memory of.” Seeing this made me feel happy. In the new American Indian Center, I can see the parts of the building that are new and how the old building was made better. I could recognize where the old parts of the building used to be and how they are familiar and full of memories—and that was also a good feeling.

I want these special places to last forever. I want the Roof Depot to be made new, to be a place where youth of all ages can hang out, do arts and crafts, and play sports—mostly where we could be safe.

When I see the pictures of what the Roof Depot could look like with solar panels, trees, and gardens, I am amazed. Instead of more pollution, we could have something new.

Seeing the pictures helps me imagine what else could be. I dream of a greenhouse on the second floor, filled with flowers, fruits, and vegetables—dragon fruit, sweet tomatoes, regular tomatoes, grapes, strawberries, blueberries, and raspberries.

On the first floor, I envision there being a splash pad and a separate space just for kids to have fun and imagine. Parents would get a special code to access it for safety, so kids could play and imagine without worries. There would be a bathroom, slides, an arts and crafts table, a hill with a big slide under it,

On the first floor, I envision there being a splash pad and a separate space just for kids to have fun and imagine. Parents would get a special code to access it for safety, so kids could play and imagine without worries. There would be a bathroom, slides, an arts and crafts table, a hill with a big slide under it, and a conference room for adults to gather and discuss how to make things even better. A market shop would offer foods from around the world for snacking when we’re hungry. This place would be called “Kids Imagine.” It would be a space to dream and imagine who we want to be. There’d be a dress-up section, so when we want to imagine a different future, we could pick an outfit and pretend to be whatever we want to be, to create the world we dream of.

Kids need places where we can just imagine because then our minds can go wherever we would like. “Kids Imagine” would be one place to do this, and meet new friends and imagine together.

I think my ancestors want me to know that I am alive right now, in this world, for a reason. They are showing and teaching me the important ways to be a good person, like being kind, caring, and loving. I think this because I know that my ancestors fought for me to be here.

They fought for the right to vote and for the rights we have today. They fought for me to be able to drink from the same faucet as other people and to sit in the same classroom as everyone else. I see the combination of my cultures as a superpower…

I know this fight is in me too.

Kamille’s story and artwork have been developed as part of Resilient Landscapes for Re-imagined Futures—a year-long pilot project amplifying the narratives of both an Elder and a Youth, and their cross-generational visions of climate justice. Facilitated by Jothsna Harris of Change Narrative and artist and science educator Julie Marckel, in support of the East Phillips “Roof Depot” environmental justice community in Minneapolis, Minnesota, to support local efforts to foster re-imagined futures. This project is made possible through generous funding from the Earth Rising Foundation and fiscal sponsorship by Oyate Hotanin.